This episode concludes our coverage of M.R. James’s masterwork ‘A Warning to the Curious‘, and we also speak to James expert Patrick J. Murphy, whose essay ‘Lay of a Last Survivor – Beowulf, the Great War, and M.R. James’s “A Warning to the Curious”’ impressed us greatly when researching this story.

This episode concludes our coverage of M.R. James’s masterwork ‘A Warning to the Curious‘, and we also speak to James expert Patrick J. Murphy, whose essay ‘Lay of a Last Survivor – Beowulf, the Great War, and M.R. James’s “A Warning to the Curious”’ impressed us greatly when researching this story.

Lewis Davies returns again to lend his voice to the readings for this episode, and an excellent job he does too. Thanks Lewis!

Notes on Remembrance Day:

When we started our two-parter on Warning to the Curious, we didn’t realise that we’d be releasing the second part on Remembrance Day.

For all that M.R. James did to honour the memory of the war dead, it seems likely that his portrayal of the First World War in this story was intended to be ambiguous, and likely coloured by his role as mentor to students from Cambridge who were amongst the fallen.

Will and I are conscious that some might feel this as an insensitive topic for Armistice Day, and I am sure that M.R. James would have felt the same way. But the podcast is ready, and I hope you agree that there is some merit in discussing how heavily the war weighed on James – as we remember those affected by war, in all conflicts.

Show notes:

- ‘Lay of a Last Survivor – Beowulf, the Great War, and M.R. James’s “A Warning to the Curious”’ by Patrick J Murphy and Fred Porcheddu (under review)

Our intereviewee in this episode is co-author of this excellent essay. Patrick assures us he will let us know when it is published! - ‘”No Thoroughfare” – The problem of Paxton’ by Mike Pincombe (Ghosts & Scholars 32)

This fascinating article (sadly not available online) explores the implications of a wartime setting for ‘A Warning to the Curious’. For an entirely different take on the character of Paxton, see Pincombe’s very entertaining essay ‘Homosexual Panic and the English Ghost Story‘ (G&S Newsletter 2)! - The Martello Tower, Aldeburgh (Landmark Trust)

Fancy a holiday in a real-life M.R. James location? The Martello Tower at Aldeburgh where Paxton meets his death is now a holiday cottage! If you are not familiar with martello towers, you can learn more about this particular type of coastal defence on wikipedia. - Beowulf (wikipedia)

Patrick and Fred’s essay (see above) points out the glaring similatiries between this story and the most famous anglo-saxon story, Beowulf. Both stories feature theft from a burial mound with a guardian. - A Warning to the Curious directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark (BBC TV 1972)

Further details about the 1972 TV version of this story can be found on wikipedia, including differences between the TV version and the original story. - A Playmobil Warning to the Curious (youtube)

For a different take on the story, watch this playmobil animation of the story created by author and James-scholar Helen Grant and her son. It is both scary and cute in equal measures! - A Warning to the Furious (BBC Radio Drama)

Another highly entertaining riff on this story can be found in this BBC radio drama from Christmas 2007. A feminist film crew visit Aldeburgh to try and psychoanalyse M.R. James, but find they have bitten off more than they can chew! This drama is not currently available form the BBC but can be tracked down on the dark dingy corners of the internet with a bit of searching. - Our visit to Aldeburgh (Flickr)

You can see some photos of the visit we made this August to Aldeburgh, Suffolk on our Flickr account. Also see below for a video of out visit. Don’t forget you can view these locations on Monty’s World, our online mapping app.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Tags: Aldeburgh, Beowulf, Fred Porcheddu, Lewis Davies, M.R. James, Patrick Murphy, Paxton, Seaburgh, Warning to the Curious, World War 2, WWII

Hi. Great to hear part 2, and I agree with you when you observe that two parts are NOT ENOUGH. It obviously can bear a great deal of analysis, which is more than can be said of most ghost stories. I still have a couple of problems. Why, at the inquest, does no-one know of a William Ager? Paxton seemed to come across plenty of traces – unless of course it was all his imagination, in which case, what/who killed him? My other question is this. If Ager was defending the crown, why did he not make sure of its safety by disposing of the narrator and Long, who both knew where it was buried? The narrator, after all, tells MRJ everything – presumably because the war is safely over by then; though what about subsequent wars?

Minor observation: that the railway porter’s action in holding open the door just a little too long echoes what happens to Carswell.

There is the question of why Long is dead. I’ve always thought that it was Ager that killed him.

Interesting point.

Maybe Ager’s reach is limited to Seaburgh which may explain why the narrator hasn’t be killed and why the narrator at the end emphasises the fact that he’s not just not been to Seaburgh since, but not even been near it

Hi,

Great episode! And it made me realise something that I’d never noticed about the story before. Now it may be nothing and I may be reading more into this than James intended, but there is something strange about Paxton’s injuries. They seem horribly indicative of Paxton falling onto his face (with the shock of impact accounting for the mouth full of stones and sand), but when the Narrator and Long see the damage done to him (and looking only once) they are standing well above him, on top of the wall looking down.

Has someone or something turned over the body? And if not, how did they get there?

This is really the best work I have heard on the topic. I always regarded this story as important example of James’ work, but I had no idea how bleak and profound the story was! What deep sadness boils there!

I don’t think that there is a suggestion that God is powerless to help Paxton; rather I think what is suggested is that Paxton has transgressed and God won’t help him. There is a suggestion of Paxton’s sinful pride, his attempting to steal a royal/divine crown, and, like Lucifer, suffering the terrible consequences. This is an alternative reading, but the strength of this story is that so many such readings are possible.

As for the BBC drama “A Warning to the Furious” – I might possibly have a copy which I might share (for purposes of academic comment and fair use only)…if asked nicely.

This story is so wonderfully oppressive and absolutely downright sinister. I could honestly gush about it all day and leave an essay of a comment here, it’s my favourite story. ‘That wasn’t my coat’ was one of those perfect moments of creepiness that genuinely bothered me.

On the whole ‘it’s the body that has to suffer’, I think Paxton means, yes, he might go to Heaven a good man, but this thing is still going to get him, there’s nothing for God to help with.

I wonder what happened when the earlier crown was discovered and melted down. Did it not matter as there was another still hidden to protect the country? Or was there no earlier Agar to protect its honour.

I stil don’t accept the idea that Agar is the thing which kills Paxton. This turns Agar into some kind of Tales from the Crypt zombie, which would be too coarse for James. Maybe the Agars were supposed to be the first line of defence with the creature only to be used in extremis.

Can anyone think of another ghost story where the victim runs or even walks towards his killer?

Have you guys read the Jamesian inspired Ramsay Campbell story?

Well, a ton of other James horror have been physical, just like William Ager. Oh Whistle had a sheet ghost, Canon Alberic had a straight-up demon, Martin’s Close the drowned corpse/ghost of Anne Clark – just because it has an effect on the world around it doesn’t mean it can’t be a ghost. James wrote very physical, sense based things, the physical manifestation of the will or anger of William Ager killing Paxton seems just fine if a sheet can attack Parkins in Oh Whistle.

Firstly I would just like say that this is another excellent podcast episode, and secondly to out myself as the main writer of the AWttC wikipedia page which I expanded from a stub, I proudly can confirm that it is over long and excessively detailed!

To Richard Leigh:

I think it is clearly indicated in the conversation between Paxton and the rector that the locals guard the knowledge of the Crown, and the collective failure to identify Ager at the inquest is just another example of this. The BBC adaptation makes this much more explicit when the rector says that despite having lived in the place for many years he is still considered an outsider and not trusted with the location of the crown.

To Mark: You asked about if “Can anyone think of another ghost story where the victim runs or even walks towards his killer?” Daphne du Maurier wrote a short story called “Don’t look now” (published in 1971, not sure when it was written though), in which the main protagonist chases after a figure he thinks is child/possibly his dead daughter, and of course it is not and he meets a similarly grisly fate. The very good movie adaptation from the 1970s has this ending in and is I think very close to AWttC in that respect.

Forgotten Don’t Look Now. Thanks

Fantastic works, guys: for my money his greatest story and you definitely did it justice. I agree that the War and James’s ambivalent feelings about it are important here: a similar point I tried to get at from a different angle in the Jamesian part of my novel Prospero’s Mirror.

One idea I had about the story: why would James have inserted the otherwise-unnecessary character of Long, and then mention that he’s dead? Is it possible that the implication is that he might perhaps have also been a victim of Ager, and that the main narrator (despite making sure he’s in a place ‘very remote from Seaburgh’ and ‘never going there’ again) is also in possible danger? After all, they both now know the whereabouts of the crown, and indeed the main narrator is apparently happy to tell others about it. We only have Paxton’s suggestion that the fatal error is actually touching it – indeed, Ager was already physically manifesting himself and trying to thwart Paxton before he ever laid hands on it himself.

This might also explain why James-as-overall-narrator is himself careful to disguise the setting as ‘Seaburgh’ rather than Aldeburgh, and perhaps why he doesn’t close off the framing device – because by not resolving or commenting on the main narrator’s likely subsequent fate, the uneasy possibility remains that the horror might not yet be over…

Ooh, that’s actually really good. I suppose we really do only have Paxton’s inferrence that touching the crown really does you harm.

Or maybe it was because Paxton touched it and took it out that he got Ager’s wrath, but perhaps Long and the narrator’s knowledge of its burying place is enough to warrant a slap on the wrist or dire warning from Ager.

It is, in fairness, a very vague ending, which after your comment I quite like, so in the end, you can really make up your own conclusion as to whether anyone else is in danger. It’s like The Call of Cthulhu, every reader is now taking part in that exploration and discovery of a dangerous secret and by proxy of closeness to it, is a target for doom.

There’s not been a bad episode of the podcast, but these last two have stood head and shoulders above the least, absolutely first class!

Very poignant as well given the timing- I never thought before about the many seeming WW1 images in the story, particularly Paxton running into the fog. For some reason the thought of Paxton’s body kept bringing this image into mind of a dead WW1 soldier, such a tragic photo (warning, not pleasant)

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_Mx-_0Wuo6NY/TIv2t0CIeQI/AAAAAAAAABI/z4KKY-xunJE/s1600/UnburiedGermanSoldierSommeWWI.jpg

I don’t think I’ve ever listened to a podcast (including the excellent HPL one) which has made me think so much about a story. I don’t have anything to add to the thoughts, other than perhaps Ager represents the spirit of war or patriotism that leads the young man to his death or perhaps he is the suffering and regret that haunted so many who returned from the battlefields and maybe destroyed them later in life.

Anyway, bleak perhaps, but a very very interesting two episodes – thank you!

I’ve always thought of this story being set in the year leading up to The Great War, and that Long was killed perhaps in the closing period of the conflict when men of older age were being drafted in due to the man power shortage.

I do think Paxton represents that generation of young men who fell during the war, he is dragged along to finding the crown (and subsequent death) by circumstances that seem to be beyond his control or full understanding, he has that same initial sense of excitement at the challenge, and then the horror sets in.

The image of the young Paxton weeping at the terror he has suffered at the hands of Ager is a powerful one, and perhaps mirrors some experiences of Monty witnessing such scenes in the aftermath of the war with friends that had experienced the front?

The quality of this podcast just made me realise how much I’m going to miss you chaps when the stories run out.

It’s intersting to compare Paxton with the meddler in Count Magnus. Both have all their possessions in storage with no strong family ties. Both get out of their depth and both suffer. The dofference is that one is returning from Sweden whilst the other is going there.maybe James simply reused an earlier plot device rather than trying to say that Paxton is fleeing abroad to avoid serving in the army.

Fascinating idea that Paxton’s injuries resemble a war wound! And you’re right, thinking of it as set in the war puts it in a whole new light.

To me, it had another echo as well: the story Marcus Licinius Crassus, supposedly killed by the Parthians by having his mouth filled with molten gold as a punishment for his greed. It seems very probable that James would have known the legend, and there’s something of that in Paxton’s death: you like digging up earth? Have more earth. Choke on it.

You mentioned in the first part that it seems like a selfish desire for gain to dig up the crown. I’d say that it’s not exactly a desire for glory in the ordinary sense; it’s more a desire for knowledge. My mother’s an antiquarian, and while they’re law-abiding people on the whole, it’s also a vocation: you dedicate your entire life to studying fragments of the past because you feel in your soul that you’re adding to human nature’s understanding of itself. An Anglo-Saxon crown is a truly fabulous treasure, not for its financial value but because of its extraordinary historical significance; finding one would be like a doctor finding a cure for a serious disease. For an antiquarian, to leave the crown buried would be almost barbarous, letting it rot in the earth when it could be found, preserved, protected and learned from. (Historical artefacts getting damaged or degrading is something that horrifies antiquarians; to spoil one is almost like killing someone.)

So by academic values, Paxton digging up the crown really isn’t being selfish. He’s just doing what any antiquarian worth his salt would feel he *had* to do. Local people having silly superstitions is no reason not to find and preserve this incredible piece of our past; they just don’t understand its importance.

…Which is why, as well as a war story, I think this is a town versus gown story. Tensions between academics and locals are a well-established thing, and in this case, what Paxton runs into is a man with a vocation even more deadly serious than his own. He also, in a sense, fails as an antiquarian: he doesn’t see what’s right in front of him, which is that the tradition of guarding the crown is, itself, a piece of history, in need of preservation, and that digging up the crown is inherently damaging the tradition.

That’s one reason why that Bible verse is so powerful. It’s threatening in its very conventionality. The Agers don’t look outside tradition to express themselves: they grimly do what’s always been done. England is my nation, Seaborough is my dwelling place, Christ is my salvation: to know who I am, ask only what I serve. The Agers live and die for their pre-ordained role … so of course they won’t forgive anyone who violates it.

Very enjoyable two-parter, for what (contra general opinion, I now realize!) I always have felt was distinctly one of MRJ’s lesser stories. I’m still far from convinced, but these two episodes did get me to think about it again, and more, and find some more interest in it.

Am I alone in having felt the TV adaptation was really good, perhaps even better than the story? In particular I thought the recasting of Paxton as older, laid off, and facing the Depression — as well as the more explicit drawing of class lines — more satisfying than the original text.

Will let it settle and read it again in a few weeks. Perhaps I’ll still come around on this one 😉

I believe Henry long died because he told of the crown’s resting place, and that the nameless narrator died soon after he told James.

Augustus Jessopp was a friend of M.R. James and together they worked on a translation of a medieval text in the 1890s. Among Jessopp’s many books was one called Frivola, a collection of supernatural occurrences (they’re not really narratives). One of Jessopp’s pieces is even entitled “An Antiquary’s Ghost Story.” But also there is a piece that may be a source or analogue for James’ “Warning to the Curious.” Hill Digging and Magic” which is included as an appendix in this pdf edition of Frivola:

http://gothictexts.wordpress.com/category/augustus-jessopp-1823-1914/

Most of the text recounts episodes of people digging up old coins (sorry, no Anglo-Saxon crowns), but it also links hill-digging with sorcery, especially this passage, which serves as a kind of warning to digging for treasure:

” ‘There may be heaven, there must be hell,’

was not a dogma first formulated in our days. Heaven for the gods, there might be; but earth,

and all that was below the earth, that was the evil demon’s own domain. The demons were

essentially earth spirits. The deeper you went below the outer crust of this world of ours, the

nearer you got to the homes of the dark and grisly beings who spoil and poison and blight and

blast—the angry ones who only curse and hate, and work us pain and woe. All that is of the

earth earthy belongs to them. Wilt thou hide thy treasure in the earth? Then it becomes the

property of the foul fiend. Didst thou trust it to him to keep? Then he will keep it.

‘Never may I meddle with such treasure as one hath hidden away in the earth,” says Plato

in the eleventh book of the Laws, “nor ever pray to find it. . . .’ ”

To cap it all off, Jessopp followed up his “Hill-Digging” piece with another in the journal “The Nineteenth Century”, entitled “A Warning to the SPR”, which can be found here on page 612

http://books.google.com/books?id=rbHQAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

An interesting inspiration for James’ story.

Interesting that the narrator refers to Paxton’s “kitbag”. Is the narrator an old soldier? (Boer War veteran, perhaps). It would be odd, if so, for him to feel any sympathy with Paxton, if the latter really was a draft-dodger, or a pacifist.

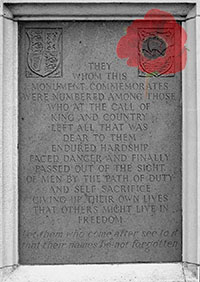

A (very) small point. Richard Pfaff, in his biography, (p247) points out that the last sentence of the inscription on the memorial was not by MRJ, but was a replacement, by the Commission which arranged for the memorial, for MRJ’s quite different final sentence.

I’m an artist and am planning to do a series of paintings based on M. R. James’ ghosts and creatures and while researching some of the stories for details and ideas I was pondering James’ text on the Aldeburgh WWI memorial and it struck me that it rather neatly sums up the fates of both Ager and Paxton.

(memorial text in all caps)

THEY

WHOM THIS

MONUMENT COMMEMORTATES

WERE HONOURED AMONG THOSE

WHO AT THE CALL OF

KING AND COUNTRY

(Ager’s call to guard the king’s crown the protect England, Paxton’s strange experience of feeling there “was a sort of fate in it, ” and “anybody would call it the greatest bit of luck. I did, but I don’t know.” Feeling drawn or called by the crown, as you mentioned in the podcast.

LEFT ALL THAT WAS

DEAR TO THEM

(Ager left the world of the living and Paxton came out to the coast and also has plans to leave for Sweden)

ENDURED HARDSHIP

(Ager endured the harsh night watch of the crown, Paxton endured Agers torments)

FACED DANGER

(Agers nightwatch was clearly a danger, having invited the cause of his death, Paxton, obviously faces danger from Ager)

AND FINALLY

PASSED OUT OF SIGHT OF MEN

(Ager “has a power over your eyes” to seem invisible, Paxton goes running into the sea mists and disappears)

BY THE PATH OF DUTY

AND SELF SACRIFCE

GIVING UP THEIR OWN LIVES

THAT OTHERS MIGHT LIVE IN

FREEDOM

(This is clearly illustrated in Agers case, it sums up his reason for living, and in Paxtons case perhaps his path of duty became clear to him when once he learns he has to replace the crown where he found it, he’s been resigned to his fate since we first meet him, and he made sure to protect Long and the narrator from touching the crown so they might leave unscathed.)

I absolutely love this story and all of you did a tremendous job rooting out the deeper significance of it, adding such richness to what is already a fine and scary ghost story. Very inspiring show and episode, well done!

I did some investigating of my own into certain things that stood out as maybe having a deeper implication but couldn’t make heads or tails out of most of it but just include it here in case someone else could take it as a lead into something further. Might be all rubbish who knows…

First the specific mention of the Paschal moon stood out, the Easter moon. In 1916 full moon fell on the 18th making Easter the 23rd that year. April 23rd is a holiday in England, Saint George’s Day. April 23rd being the day of George’s martyrdom.

I find there are some parralels between Paxton and Saint George. Saint George is a military saint and there are clues that Paxton had indeed served in the military (as you all mentioned), these being his trench coat developed for and issued only to officers in the first world war, George himself was an officer in the Roman army. Another bit of evidence is his Paxton’s kitbag.

At a young age George lost his parents and it is mentioned about Paxton: “the fact is he had nobody.”

These lines of Paxton’s “The Church might help. Yes, but it’s the body that has to suffer.” (and suffer he does, the whole story) to my mind sufficiently align him with the theme of martyrdom seen in the legend of Saint George.

There is also the Invocation of Saint George which ends with the line “Valiant champion of the Faith, assist me in the combat against evil, that I may win the crown promised to them that persevere unto the end.” The words “win the crown” of course stand out here in relation to “Warning.”

Also, there is a link that further supports the Beowolf theory which is the popular portrayal of Saint George riding out with his lance to defeat a dragon (the setting of the fight being along the coast of a great lake and often depicted in paintings looking like a sea coast).

One last possible link, though a stretch, is that, having mentioned that he was planning to go to Sweden soon and knowing that James spent some time there he may have known that in the Church of St. Nicholas in Stockholm houses a large, late medieval statue of Saint George (attributed to Bernt Notke, prominant sculptor and painter of his day, as his most famous work) which is supposed to house some bones of George as relics.

That’s about as far as I could get with the Saint George connection. Maybe someone else could take that further or poke some holes in it all.

As far as some actual Easter connection itself is concerned it could play on some Anglo-Saxon angle in the story. Pagan Anglo-Saxons held feasts in honor of Eostre and one of her symbols was a rabbit, so in that lies the whole rabbity Paxton thing as well.

On ancestry.com I found a record of a William Ager, of Palgrave, Suffolk, England (about a half hour’s drive from Livermere, hour from Aldeburgh), who died in 1891. Not to say there is any connection with that specific person but as we know James’ often drew on actual local names to incorporate into his stories (Ash Tree, Martin’s Close) and this just shows that there were Agers in that region.

Next, as far as any evidence that James intended Paxton to be viewed as some kind of traitor to England, I found a lead on a James Paxton on a genealogy website. http://tinyurl.com/k7phkqn This Paxton seems to have thrown in with Cromwell and “officiated” at the execution of Charles I. As we’ve seen in other stories, M. R. James goes back to the English Civil War for inspiration and perhaps he did with “Warning” also. From a Geneaology.com forum I found searching for James Paxton: “James Paxton was born in central England, attached himself to the army of Cromwell, and was probably the Paxton who officiated at the execution of King Charles. After the Restoration, James and his family fled to Ireland, and settled at Ballymoney, in County Antrim, Ireland. Here he found aid and comfort from his presbyterian allies.” Not any kind of official record, but could be a lead if someone was so inclined to look further into it.

Anway, like I said, could all be rubbish, and also I’m no “scholard” and get most of my info from Wikipedia, so…

Thanks guys, I look forward to new episodes and to rereading all of the stories and relistening to old episodes! Great stuff!

Until I heard this podcast (which was great), I had never, bizarre though it may sound, associated the figure following Paxton with William Agar. Instead, I always thought of it as a kind of elemental guardian – some spirit created from or by the Kings whose crowns had been buried or an amalgamation of all the Kings. I suppose this theory hinges on the Kings’ sovereign power, that their power to rule and defend was somehow harnessed magically in this figure by the ritual of the burial in order to protect the land against invasion as per the legend.

Having listened to all this, I can see that this makes much less sense than the guardian figure being Agar (duh!!!) – interesting how we all interpret things in different ways!

Paxton as a rabbit marks him out as prey, maybe also a sacrifice/food.

I’ve read this several times before. The last time I noticed the imagery on the beach seemed to evoke war images I’d seen. Paxton’s running after his friends waving his stick reminded me of both a war charge and a kid playing at a war charge. He’s skillful in evoking the feeling rather than making it overt.

The warm atmosphere of male friendship and bonding becomes the instrument of Paxton’s death. Made me wonder if James was questioning to himself whether the comfortable traditions he loved so much had been used to ensure the young rabbits would follow each other onto the battlefield shouting to each other and waving their sticks.

I don’t think James’ comments about God providing comfort but not help were atheistic in nature; he was simply capable of a individual and nuanced view of the intersection of his God, spirituality and life.

Sort of like ghosts and spirits are of a lower court of law closer to the earthly Pagan/Old Testament ideals while God is of a completely different order of magnitude. King and Country may have a spiritual resonance but ultimately they are of the physical world, not Heaven’s.

The story, as you say, takes place at Easter. Does this make the rabbitty Paxton into an Easter Bunny ? There’s often confusion in folk tales between rabbits and hares.

I sense the material for a folkloric thesis – as long as someone else writes it.

These podcasts are uniformly excellent but this one, part two, is especially good and I love the conversations you get rolling!

A bunch of my own thoughts on this one:

Wow. I never knew the original setting date so I never made the connection to the Great War, but even then it’s always been clear this story is one of the most dark and hopeless so I’m not at all surprised. There’s a very deeply emotional sadness to it that isn’t present in even the grimmest of the others.

For the question of Paxton being almost led to find the site, I figured all the hints and fate indicate that the ghost wants to attract a new guardian and hopes Paxton will be that guardian, but once it becomes clear that he is only interested in digging the crown up, it becomes hostile.

In regard to being set during the War, that would definitely cast doubt on Paxton’s character that a fortnight before this he was ‘so happy’. If he was a vet with PTSD he probably wouldn’t have been happy at any point since his service and if he was a draft dodger or conscientious objector, what a self-centered pig he is, yet James writes him ultimately likeable. So what if this was set slightly before the war? Ager knows war is coming but Paxton has so far managed to avoid any thought of it and is blithely going along without a care. It could be an allegory for citizens who before the war refused to believe there was a threat until there were bodies, especially considering Paxton’s eventual demise. Your comments about his fatal wounds being artillery-related made it seem even stronger. The mist could be a shadowing of gas attacks. Paxton’s name might be indicative of the shattering of peace the war brought. The failed attempt to escape to Sweden/neutrality would represent no choice for staying out of it. War is upon you: you must be prepared to defend in any way possible (crown).

Either that or as you say it is set in an alternate 1917 where there was no war, yet is saturated by it because of James’ frame of mind. Even the kit bag and trenching phraseology could be argued in any direction as to whether it’s set during the war or is only seeded with war references because James had the war on his mind.

Apologies to Patrick but I totally disagree with the interpretation of the title as a warning meant for Paxton that is too late. It’s the first time in this podcast that I suddenly felt like we’re digging WAY too deep into stuff. I do think the idea that Ager’s obsession with protection “the crown” could be a nice metaphor for sacrificing young men to hideous deaths in aid of protecting a crown, that is England, and also the helplessness of mentors standing by trying to be cheerful while knowingly feeding youth into the meat grinder. Having been one of those mentors, MRJ was probably more likely to feel a pang of pain of loss instead of pride when he passed that memorial.

And lastly, thank you for admitting the last shot of Black Adder Goes Forth made you cry. It makes me cry whenever I watch it.

Oh yeah! I loved the video tour, thanks so much for posting that! And when is the CD coming out of the music? As always, it’s great.

RIP Peter Vaughan. Nice to see A Warning to the Curious being mentioned in his BBC obituary today. Excellent in Alan Ayckbourn’s Seasons Greetings as well. They say you’re sophisticated if you hear the William Tell Overture and don’t think of The Lone Ranger, the same applies to Peter Vaughan – if you see him and think AWttC rather than Porridge.

Apologies if already flagged up in comments but the (TV) film referred to in the discussion around Gallipoli/WW1 is “All the King’s Men” {1999} with Davis Jason and us very good.

Excellent debate & discussion around this classic MRJ tale.

I of course meant David Jason!

I listened to the two episodes today, having read the story immediately beforehand (and having just rewatched the seventies tv adaptation). These were my favourite episodes so far with so much insight into the themes of this compelling (yet often depressing) tale and also the motivation of WW1. Indeed, the idea of sacrifice, war horror and trench digging taken from the war and presented in the post war years got me thinking of the recent Peaky Blinders series where the protagonists all display signs of shell shock and are often transported back to their tunnel digging memories. I’m now looking forward to seeing this performed in October by Robert Lloyd Parry!

Great episode(s)! I enjoyed your discussion of how the recognition of archaeology, as a discipline, was likely viewed at the time of the story.

It brought to mind another archaeology reference: one of James’ more humorous, or at least most straightforward in pursuit of humor. I believe it’s in the original text, certainly done memorably in the BBC production, where Squire Richard compares Fanshawe’s interest to Baxter’s, saying something like ‘so you fancy yourself a bit of an archaeologist as well’, to which a flustered Fanshawe retorts “I am an archeaologist…I’m a doctor!” to which Squire Richard mutters ‘I really should have you check out this stiff neck’ or something similar.

Sorry, I should say the above reference is from “A View From A Hill”

I’ve wanted to comment on this great episode pair for a while, and I’ve just been inspired to get around to it.

The interpretation of literature is certainly an enjoyable exercise, and hearing the views of others is always an education. In this case, with reference to the Great War, I think that things went a little further than the text supports. For me, the first rule of such endeavors is that one must stick to the text – the text is the only evidence we can go by, because the text creates its own universe, and we can only live within it. So interpretations that speculate beyond the evidence of the text just don’t seem satisfying to me.

The one example I’ll give is in reference to the word ‘scolard.’ In supporting the Great War interpretation of the story, it was suggested by one of our fine hosts (if I remember correctly) that the word ‘scolard’ might be a portmanteau of scholar and coward. In fact, ‘sc(h)olard’ was a legitimate dialectical English word. I remember seeing it in Silas Marner (also used by a village yokel), and an online search produced an example from one of Bulwer-Lytton’s novels. There’s actually a technical name in linguistics for the addition of a final consonant to a word that ends in a consonant – it’s not unique to this word. I was inspired to write this comment by just having seen it in The Scarlet Letter, of all places. Hawthorne puts it in quotes, suggesting that he could trust that his reading audience would recognize the word and its common context.

General rule: the simplest (and least imaginative) answer is probably the best.

Love the podcasts, and look forward to each new one.

A new find. Sheridan Le Fanu’s ‘Sir Dominick’s Bargain’ includes a ‘scholard,’ and also a ‘sould’ for ‘soul.’

I’m a bit late to the party, but this is how I read the use of ‘scholard’. Is it not just a way of showing that this character is an uneducated ‘village yokel’, as you put it? Similar to how people say ‘demond’ for ‘demon’.

I don’t think the two elder characters in the story would have been quite as helpful towards Paxton if he really was a deserter or a conscientious objector.

I’ve recently listened to Derek Jacobi’s reading of this and I’m taken by ‘scholard’ or scolard being a version of ‘schooled’ such as ‘you being schooled in this field’ or ‘you being a scholar in this field’. It’s a bit late to comment but I do regularly ‘re-listen to my favourite episodes.