This week Will and Mike explore the borders between psychedelia and twee when they crack open The Five Jars, Monty’s only novel. Prepare yourself for enigmatic springs, helpful trees and cantankerous cats – and two very confused podcasters.

This week Will and Mike explore the borders between psychedelia and twee when they crack open The Five Jars, Monty’s only novel. Prepare yourself for enigmatic springs, helpful trees and cantankerous cats – and two very confused podcasters.

Show notes:

Parents beware – Will drops his guard and utters a foul-mouthed profanity at 12:48. Chapter one was a real struggle at times.

The full text of the Five Jars, courtesy of Thin Ghost.

We used Peter Yearsley’s Libravox recording of Five Jars for our readings this week, with sound editing by Will.

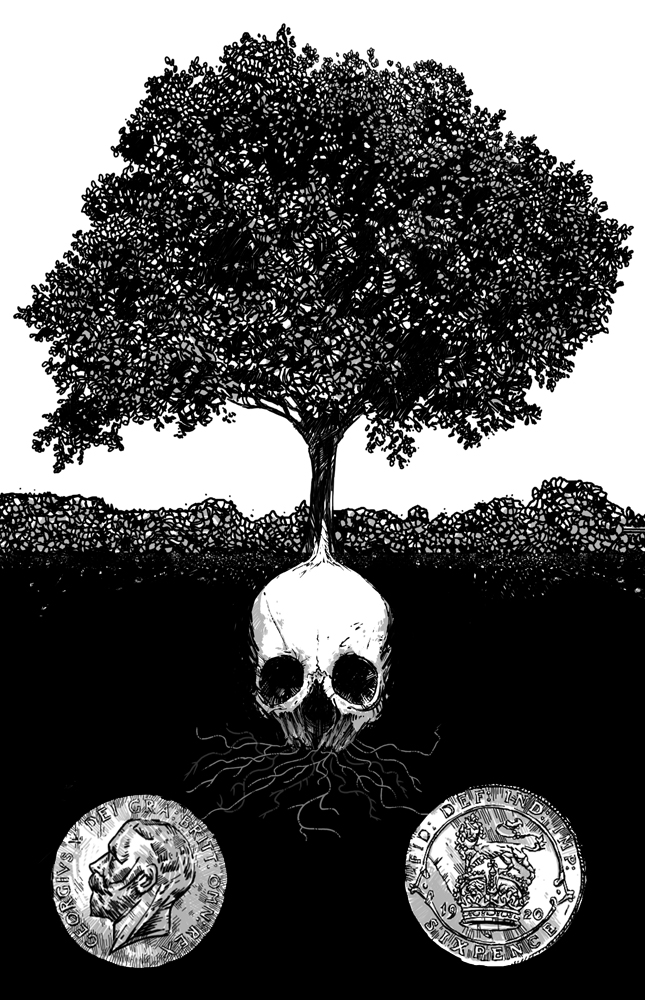

Alisdair Wood’s excellent illustration for The Five Jars also appears on this month’s Ghosts and Scholars Newsletter (subscribe!). Why not check out Alisdair’s store?

If you’d like to see one of Robert Lloyd Parry’s performances in Oxford, Manchester, Newcastle, Cambridge or Hemmingford Grey Manor, do contact him directly.

And finally, did anyone else think of this when they heard about the bat?

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Hello, Chris Ebert pointed me to your podcast. You’ve done a lovely job, filling in background on The Five Jars. I felt, when I read it, that it seems peculiarly unfinished, as if it was the sketch for something that he wanted to make much bigger and more complex, but found that he lost his way once the narrator had explored all the vials.

… and thanks for your kind words.

I had thought of recording James’s Thin Ghost collection, but was put off by the first story, which not only needed Irish accents, but (what I think as…) layered them, where one character (one voice for me to create), quotes another character (a second voice to create, but coloured by the first) .. and sometimes with a third layer. I couldn’t work out a way to handle it.

Peter

Thank you for including this wonderful story of James’. I always felt, that while it isn’t one of his ghost stories, it has the good old Jamesian character, and even shows more of what kind of person he was. I think one thing it reveals is his interest in communicating. Not only does he indicate that he took great pains to learn Latin, as we all know, but he also seems to be sensitive to what he may be hearing from inanimate objects, plants, and animals, and to actually gamble on what they might be telling him. Now there’s a lesson for children.

I would have said the influence of E. Nesbit, no slouch herself at spooky stories, was strong on this. I detect elements of “Five Children and It” and “The Phoenix And The Carpet” in the tale.

I’m glad you guys are covering this story, as thoroughly as you are! I know I would have _loved_ it as a kid; unfortunately I didn’t encounter it until my late ’30s.

I strongly agree with Laurence (#1, above) about the Nesbit vibe. (I will confess that, coincidentally, for many years now I’ve always pictured the Psammead as looking _exactly_ like M.R. James himself…)

The beginning sequence of the narrator’s wandering through the landscape following peculiar clues and customs reminded me quite a bit of Machen’s “The White People” narrative, actually — only the way a middle-aged don would feel and write about it, rather than a twitchy mystic trying to write like a young girl.

Very much looking forward to part two — thank you!

It has all the hallmarks of fairy folklore and of what we nowadays call shamanic practice – the realisation that everything is alive and communicating, and that fairies and other spirits may not always have the same attitudes and agendas as humans.

In shamanic practices, people Journey to the Otherworld(s) via the roots of trees, springs, bodies of water, and caves, and the ritualistic ingestion or smearing on the body of substances the spirits have guided you to allows you to see and communicate with the residents of this other reality. You see it all over fairytales and myths – don’t eat the fairy food, or you’ll be trapped in the barrow forever; smear the ointment on your eyes and you’ll see the fairies; and Alice In Wonderland uses all those tropes to great effect.

I find myself wondering to what extent people did go tripping before the 20th century’s war on drugs. Richard Davenport’s The Pursuit Of Oblivion points out just how easy it was to get “medicinal” opiates over the counter in Victorian Britain, while at the same time Respectable Society was freaking out about absinthe, and that women were sending heroin gel from the local chemists to their loved ones in WW1, which led to a ban.

I forgot to mention that folkloric fairies and witches can’t abide iron. It seems to be considered protective against them in some way that no other metal is, much as silver protects against vampires and werewolves (I wonder why silver’s protective properties are so rarely seen in contemporary vampire fiction?).

There’s been some suggestion that this is a folk memory of iron’s superiority in war against bronze weaponry, which goes hand in hand with the Victorian idea that fairies are a folk memory of an indigenous people who fled into the wild spaces when the Celts invaded. I believe the Irish mythology around the Tuatha De Danaan’s invasion of Ireland and their aggressive war against the indigenous (and cthonic) Fir Bolg was held up as evidence of this.

Now we know that most Britons have plenty of paleolithic British dna, and that the idea of waves of mass migration doesn’t fit with our overall genetic make-up, maybe it’s reasonable to assume that, given how resource-heavy iron working is, and how much expertise is required to create weaponry (swords being believed to have their own souls, and being handed down through generations), efficient farming equipment, and essential utensils (pots, cauldrons, skillets and knives also being handed down generation to generation – I cook with my husband’s great-grandmother’s skillets!), iron was respected simply because it was precious and central to a huge cultural leap forward.

That got long and rambling.

Just a little correction – in fact, studies of ancient DNA have shown that the Neolithic farmers of Britain (ancestors of a migration from western Anatolia) were largely replaced by newcomers with Steppe ancestry. This is usually associated with the Bell Beaker Culture, and the evidence is now very strong. I recommend the Bell Beaker Blogger web site for discussion of the evidence. Also the Eurogenes blog.

And now, back to ghosts ….