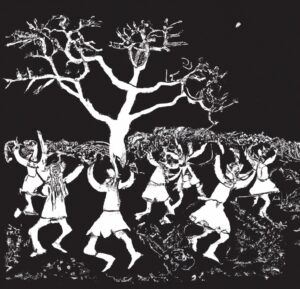

This episode Mike and Will explore freaky folk-dance, village-based villainy and Cotswold chicanery in Eleanor Scott’s awesome Jamesian folk-horror tale Randalls Round!

Big thanks to Kirsty Woodfield for providing the readings for this episode.

Show notes:

-

This article contains some biographical information as well as plot summaries of the stories that appears in Randalls Round, her only collection of ghost stories. You can also see a photo of her here.

-

Helen Leys started using the Eleanor Scott pseudonym when she published this controversial novel that exposed the dire experiences of teachers and girls within the English high school system.

-

Eleanor Scott was a student at this ladies college in the days before women were allowed to take degrees. The Somerville website contains some charming photos that give you a sense of what life was like for students at the time.

-

At the start of Randalls Round, Heyling and Mortlake discuss the folk dance revival that was then in full swing. This article describes that revival. Note the reference to the Headington Morris dancers who get a special mention in this story!

-

This 1921 book popularise Murray’s witch-cult hypothesis, the idea that the people persecuted as ‘witches’ in Europe may in fact have been involved in a survival of a pre-Christian pagan religion. Although her ideas were widely dismissed by historians, the ideas of ‘hidden’ folk/religious practices enduring in England, hidden away from the eyes of religious authorities, captured the public imagination and sparked the sort of debate that Heyling and Mortlake are having at the start of this story.

-

Aaron Worth suggests that the ‘volume of a very famous book on folk-lore’ that Heyling reads in this story would be The Golden Bough, Frazer’s influential multi-volume study on comparative religion, first published in 1890.

- Morris Dance as Ritual Dance, or, English Folk Dance and the Doctrine of Survivals (open.ac.uk)

This article by Chloe Middleton-Metcalfe explores the origins of the idea that folk dance originates in a survival of pre-Christian belief. -

In this episode Mike mentions the Broad, a Cotswold folk custom that bears some similarity to the activities that Heyling witnesses on the village green.

-

We found it hard to discuss Randalls Round without repeatedly returning to this iconic 1973 British horror film!

-

The village of Randwick in Gloucestershire is at the top of Will’s list of possible real-world locations that may have inspired the fictional village of Randalls. As well as having a similar name and large mound to the north west, it even has its own curious folk celebration known as the Randwick Wap!

-

This Instagram account celebrates the weirdest (or should that be wyrdest?) elements of folk customs and traditions. This group of Morris men parading a strange, monstrous effigy seems particularly reminiscent of the events of Randalls Round!

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Tags: Cotswolds, Eleanor Scott, Folk-horror, M.R. James, University of Oxford

Antiquarian folk horror just in time for the 12 days of Christmas(ommar)- get in.

Interesting to note that the name “Randall” holds origin in a mix of the Old Norse words “rim” and “wolf”…

so Monsters Inc was only a little misleading in that regard.

Have a good one lads and ladies- joyeux noel for all!

Were you perhaps thinking of the Doctor Who story The Daemons, and the pub “The Cloven Hoof” at Devil’s End?

I wonder, with my nasty suspicious modern mind, whether the unreasonable success at research might be ascribed to Powers that actively want this chap to be led to break in and let them out – as you suggested with the villagers possibly leading our hero later.

The Cotswolds police arrive… and say “having a nice evening, Chief Constable?”.

Randalls Round is available on Kindle at £2.99. If you have Kindle Unlimited, it’s free. Even more of a bargain!

Digging is just a hard NOPE. Everywhere and at all times.

For the part in Latin, you have to read the U as a V, so it’s ‘convicted and burned.’

You can see the original dustjacket here: https://www.dustjackets.com/pages/books/6231/eleanor-scott/randalls-round

It definitely looks like a nice children’s book.

Good as Kirsty’s rendition of the story is, Nunkie have a wonderful reading of the whole story here. https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=vBO-5IDgSmM

As a long-retired Morris dancer I’d say:

(a) The middle-aged blokes who dance Morris proably started as young blokes, kids even, and stuck with it. It’s a social activity, after all.

(b) A lot of women dance Morris and have done since the days of Mary Neal and the Esperance Girls’ Club: https://www.maryneal.org

(c) I fear you may have been overthinking the blackface aspect a bit. Historically performers have dressed up, adopted stage names and altered their appearance; this still happens even when the audience are their friends and neighbours who know them well. Once “on stage” they play a part, temporarily become somebody else. Blacking-up one’s face was a disguise/transformation easily achievable with materials at hand — all you need is a chimney — and I doubt that your average rural dancer in the 1920s, let alone the preceding centuries, was much preoccupied with the dynamics of colonial oppression while applying soot to his face. Things have changed.

P.S. Nice for a change to hear your take on a story I’d only recently read (via the British Libary reprint) and I agree with you about “Celui-là”. Keep up the good work.

Can I be the first to mention the (rather good) Mark Gatiss version of Count Magnus?

Aside from that, thanks for introducing me to this excellent story, another forgotten classic of folk horror, which, along with HR Wakefield’s ‘The First Sheaf’, puts me in mind of The Wicker Man. It made me wonder what other lost treasures are out there, waiting beneath the topsoil like the beast in Blood on Satan’s Claw to be rediscovered by the unsuspecting modern reader…

I was a little let down by this one, it wasn’t bad but it was terribly bare. The antiquated writing was a nice, almost Jamesian touch, but unlike one of his tales, there was little else in the way of fusty detail or methods of descriptions to really give it character. I’d say the highlight of the story is the town square dance and the beast skin falling onto the “victim”, that was very effectively described.

I think the problem, if it is a problem and not just a product of age, with the story it does miss a lot of the dramatic beats or expectations you guys mentioned. Nothing or no one is really set up or hinted at. It very much is just “man goes to small village and sees something weird”. I fear that was the intent–the horror is simply “what if this happened?” without a better narrative or flavourful description behind it.

Hey guys.

If you’re going to now do ghost stories written by women, why not cover “The Phantom Coach” by Amelia Edwards?

One of the best, for sure.

I encountered mumming before I ever read this story, because my parents were mummers. It was in the early 70s in Colchester, and linked to the local folk club. My dad was St George, but he took for his inspiration Julian and Sandy from Round the Horne. So the had a sword tied with a pink bow and a pink number 4 on the back of his costume (a further reference but this time to Bobby Moore, COYI!). They a largely did historical plays, but my Mum also wrote one which was performed at Essex Uni’s theatre. It involved political people of the time, including Ted Heath pulling a row of plastic ducks behind him, and Jeremy Thorpe. Mum played the Doctor, who comes on when someone has died and brings them back to life with a great big pill, very much like Miracle Max in The Princess Bride. It’s the doc who often wear the plague doctor’s mask.

With regards to black face, I think there’s only one Morris side that still applies it in the UK. All others now use blue, purple or perhaps green (also used for Green Men celebrations at May Day, a whole other kettle of dubious lore). But the origins of the black face are quite so clear. Some might come from Moorish origins, perhaps the origin of the word Morris too. But also many of the similar folk festivals have the origins in labourers parading through the towns for a few extra pennies or pints, typically in periods when they had less work such as winter time for farmers. One of the professions was chimney sweeps and they naturally had black faces from their work and so applied soot to themselves in their parades. That said, there’s still no excuse for it, even if it can claim a separate origin from slavery.